A painting and a sculpture walk into a bar.

Some notes on Roughwork, an exhibition by Heather Rule and Rodrigo Marti

0. Preface.

There’s a read of this exhibition that has always been clear to me. A reading whose themes are not necessarily easy to articulate and which the artists were tentative to acknowledge at first, but that none the less has been apparent to me from even before the exhibition had a date. The reading stems from what I perceive as shared methodologies, materialities and instincts. Perhaps I should clarify. I have for better and worse existed in the limits of both productions for a while, and I have in the process become fascinated by their relentless insistence on themselves. That is to say, for both of the bodies of work on display, the recurring imagery, and the frequent migrations of these images in form and strategy, is in many ways the engine that drives the movement of the work.

1. On language and translation.

I distinctly remember a conversation I had over a decade ago, during a seminar on contemporary art I was somehow a co-facilitator of, where a friend and I went back and forth with a few participants about the purpose of capital-A art. In all honesty, I don’t really recall my position in the argument, and I doubt with sincerity that it was original or interesting in any way, but I do recall my friend hesitantly insisting to the group the possibility of contemporary art functioning as a branch of communication. This is of course not an unusual proposition. Many undergraduate visual culture degree courses are dedicated to the subject. As a matter of fact, much emphasis was placed during my formative years in art educational institutions on the importance of semantics in image making, and it is with fondness that I recall discovering the possibility of meaning through the re-arrangement of visual elements (simultaneously a revelation and a bore back then), and one that I unfortunately continues to plague my thoughts during visits to the museum and my therapist’s couch.

I bring this up because, in my original attempts at verbalizing the underlying threads of this exhibition, language immediately jumped to the tip of my tongue. That’s not entirely true, and since words will prove important in this, let me be explicit: the idea of vocabulary did. And even more specifically, the idea of inventing a vocabulary. A few years ago, and no doubt a result of those semantics-filled days of yore I mentioned a few sentences ago, I joined a Linguistics 101 course out of a desire to acquire further education. (As an aside, I would strongly encourage everyone to do this, not only because, as I was told at the time, these are often considered to be bird courses in post-secondary education, but because they offer excellent tools for comprehending the world.) You see, I grew up in a Spanish-speaking country in Latin America, and as such I was subjected to “language” classes throughout the 11 years that are traditional in the country’s schooling system. These years were devoted to understanding the rules of the Spanish language to levels that often felt unnecessary to me, but that in retrospective examination were meant to offer an understanding of the construction of the social world that we inhabit; and while this is generously an impractical approach, it certainly has (maybe) helped my understanding of meaning in the world.

And with that expanded understanding of language, the time spent with these two bodies of work made my thoughts rapidly start to drift towards the linguistic notion of language acquisition. In the aforementioned Linguistics 101, I learned that language acquisition is understood to function most effectively by immersion at an early age. We develop simultaneously vocabularies and intrinsic understandings of grammar by a desire to interact and by being exposed to people who understand the rules of the language we are trying to learn. Of particular interest is that being able to communicate effectively in a language relies by definition on an agreement of said language existing a priori. Back to my early story about the contemporary art seminar, the thing that always has felt like a challenge when thinking back to the conversations was the intrinsic understanding that, as humans in front of art, we share degrees of visual understanding but have not in fact agreed on how they function as a system. In contrast to that anecdote, I believe that in the space of this exhibition, two attempts are being made at creating languages, and while the work presented here is by no means a grammar, it allows a kind of codex into the larger bodies of work of both Heather and Rodrigo. It also allows for an unusual proposition. A double translation of sorts. An ability to approximate the development of a novel language by use of a third, equally novel one. It is perhaps now more common to see cases where language acquisition models in bilingual households often result in unique dialects for children. Ephemeral artifacts that provide insight into the functioning of each of the source languages but also of their potential to expand each other. I believe this is now an opportunity afforded (albeit in a very primitive and restricted way) to you here.

2. Personal myth as a source of vocabulary

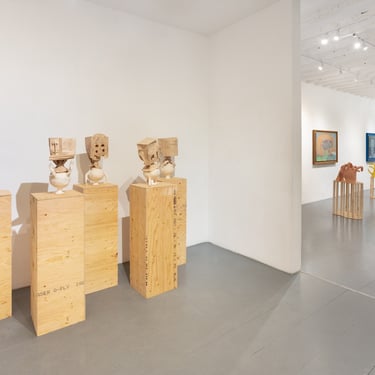

Let’s dig then into the point of entry for this complicated setup that I’ve laid above. Which is a recurrence of motifs in each of the bodies of work present in the space (and I recognize that the curated samples on display may in many cases be perceived as only superficially showing these recurring images). In both cases, the repetition, iteration, and frequency of repeated imagery is hard to ignore. It is important to note that this repetition that I’m pointing out is not about style or broad visual references, instead it signals a kind of internal logic that, to me at least, feels bigger than thematic. Early in my getting to know Heather, for instance, she showed me some drawings she had made years prior and which she intended to make a print of; there is within the show today a variation of that idea (albeit in a very different form). Similarly, I recall the first time I asked Rodrigo about an image that I had seen many times before in sketches and drafts and that, at the time of my question, had become a large painting. It is simply something I often return to, he said. I won’t dig into the origin of these images, that seems a task too big and unproductive at this time (go talk to the artists!), but I find it fascinating that both artists have settled on something that to me evokes something akin to a bestiary. This reference may seem loaded, particularly as a lot of the work here resembles creature-like depictions, but because I believe these images function as indexes for self-contained scenes, the invoking of self-mythologies seems appropriate. I’m also immediately thrown to Borges and his reimagining of the form as medium in the “Manual de Zoología Fantástica,” and the possibility of expanding language by expanding definitions.

3. Communication breakdown/buildup.

I have already hinted at the limits of this reading. A set of languages being created, independent of shared understandings and the idea of trying to devise meaning from an attempted learning of both of them simultaneously, sounds like the setup of a bad joke. It also actively fails to acknowledge the individual drive of each artist, both of which are complex and grounded with their own preoccupations about the internal repetition, recognition and dialogue their bodies of work have. And yet, I cannot shake the feeling that the conversation happening here is unique in its resemblance to an active form of live interpretation. Maybe I’m too close, and maybe it is an impossible ask to try to find meaning in a work via a different work, but I’m reminded now of a quote I heard from my mentor, Antonieta Sosa, that Venezuelan conceptual artist Claudio Perna used to say: “That which is recurring is contemporary.” This is an observation I always heard as meaning that when different practices shared themes or strategies, it is because they share an underlying understanding of the world. And so maybe this isn’t so wild an ask and maybe the punchline to the joke are your first words in this hybrid visual creole.

julian higuerey nunez